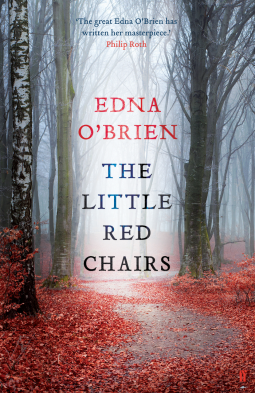

The Little Red Chairs by Edna O’Brien is a fictional portrait, a ‘what if’ scenario: what if a war criminal, a Balkan war lord, was on the run and pitched up in a small town in the West of Ireland. What if the locals took him at face value. What if one woman saw him as a way to bring a child into her childless marriage. What if his true identity was revealed. What then… would happen to the woman. This is the story of Fidelma, to reveal more about her would be to giveaway the drama of the book. She is a sad character, unsatisfied with her lot, reaching for the unattainable and ultimately suffering for her need.  This book has attracted some outstanding reviews, but I hesitated. It sat for a while on my Kindle before I read it, I think because the subject matter is depressing and intimidating. O’Brien’s writing is at times flowing and lyrical especially when describing nature, at times her structure is a little wavy and the story a little flabby. Some passages are horrifying in their brutality, the war flashbacks are vivid. I find violence, when left to the imagination, more effective than violence written on the page or acted on stage.

This book has attracted some outstanding reviews, but I hesitated. It sat for a while on my Kindle before I read it, I think because the subject matter is depressing and intimidating. O’Brien’s writing is at times flowing and lyrical especially when describing nature, at times her structure is a little wavy and the story a little flabby. Some passages are horrifying in their brutality, the war flashbacks are vivid. I find violence, when left to the imagination, more effective than violence written on the page or acted on stage.

I never really settled into reading this book. It is split into three parts, each with a different personality. The portrayal of small town life in Ireland in the first half was so full of sketchy characters I got confused. I longed for a simpler format to allow the moral dilemma to come through. In part two, Fidelma is in London, searching for healing, and for answers. She cleans a City tower block, and works in a kennel for abandoned greyhounds. At The Centre, where Fidelma goes for support, we hear the stories of abused refugees and asylum seekers, they are victims of war, genocide and physical assault and sexual abuse. For me, their stories sit uncomfortably alongside Fidelma’s own self-created dilemma and, I think because of this, I was left oddly untouched. In part three, Fidelma goes to see Vlad in The Hague at the war crimes tribunal. I admit to not understanding her motivation in going there, but it is a conversation in a bar with a victim of genocide which finally prompts Fidelma to complete the circle and return to Ireland to see the other victim in all this – her husband.

The power of O’Brien’s topic is undeniable. Is it a comment on our gullibility, how we can all be taken in by appearances; or a comment on how we avoid confrontation, not wanting to be the person to say the difficult thing, the one thing which afterwards people say ‘I thought that too.’ It is also a comment on a society which punishes and isolates the victim.

If you like this, try:-

‘Dominion’ by CJ Sansom

‘The Aftermath’ by Rhidian Brook

‘A Long Long Way’ by Sebastian Barry

And if you’d like to tweet a link to THIS post, here’s my suggested tweet:

#BookReview THE LITTLE RED CHAIRS by Edna O’Brien via @SandraDanby http://wp.me/p5gEM4-1TY